Applying Pacifist Insights to Abortion

by Rachel MacNair

I’m a Quaker, and Quakers are pacifists. We (officially, the Religious Society of Friends) join Mennonites and the Church of the Brethren as the Historic Peace Churches. Membership in any of these churches puts a person in good shape for getting legal conscientious objector status when drafted for the military.

As such, I’m accustomed to the style of arguments that are used against pacifism; I’ve written Explaining Pacifism, designed for a pro-life audience. It makes the basic case and addresses the most common arguments.

Yet many Quakers make an exception to the rule against killing human beings, thus going against pacifism, as long as those human beings haven’t gotten around to being born yet.

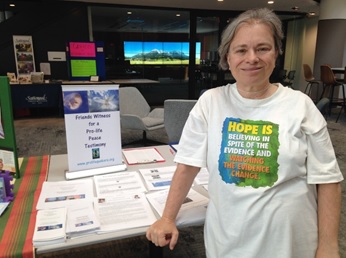

My branch of Quakers (FGC, Friends General Conference), is so bad on this that I often face hostility (or steadfast ignoring) when I bring the topic up. FGC’s magazine, Friends Journal, last August published a piece advocating Quakers take a pro-abortion stand. They were pleased with themselves that this kicked off a formal post-Dobbs re-examination among Friends. But they haven’t published an article with alternative thoughts, and they turned down the one I submitted for consideration. It’s the evangelical branch, with its strong pro-life tendencies, that primarily sees to it that Friends are “not in unity” on the abortion issue.

Since our national lobbying group, the Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL) is formally conducting this re-examination, a process asking Friends whether FCNL should change their neutral position, I’ve therefore been more actively trying to educate Friends. FCNL’s decision is to be made this November.

Fortunately, FCNL’s policy committee did give me a half-hour Zoom meeting to make my case, and I thought that meeting went quite well. But the questions there, along with the questions and arguments throughout the years, suggested three problems to me.

Problem 1: Extreme Cases

Many inquire about the strange and extreme cases, for both pacifism and abortion. These are usually isolated and often fictitious cases that don’t happen often. Sometimes there are responses directly to this; I give several on the madman chasing your mother with the knife. An excerpt:

In order to work as an example, the situation needs to be stripped down to its simplest components. Such is the nature of violence; it thrives on over-simplified thinking and withers with complicated reality.

Does this madman have a mother who will grieve his passing? Does he have a following that will avenge this death? Is he a police officer so that the weight of the dictatorial government will be coming down on you?

Why is it that a person whose mental illness is so dangerous is out on the streets – has society done its job in restraining such a person? How was it you were able to ascertain quickly that he’s insane – is he maybe drunk or high instead? Or simply off his medications and will be fine once he gets back on them? Has he recently suffered a trauma so that one quick distraction and a listening ear would solve the problem? Is he following a habit so that going contrary to his victimizing script would throw him off balance?

In any event, we haven’t identified the actual need. There is no need to kill or severely injure the man; there is a need for emergency restraint.

An example with abortion is the baby that’s going to die soon after birth, having some medical condition incompatible with life once the umbilical cord is cut. Yet isn’t it obvious that having the baby born and dying in mama’s arms, surrounded by love, is better than having someone reach up inside mama and cut the child into pieces? There are studies that show better psychological outcomes for families who go the holding route, but really, do we need studies? Isn’t it obvious as soon as it’s said that way? The problem is that people think of abortion as simply terminating the pregnancy. But as with violence in general, being familiar with what actually happens is often enough to make the violence seem less appealing.

But then there’s the observation that extreme cases are, by their nature, not common. So the second answer I gave dealt with the opposite – the cases that are more frequent. What about sex-selection abortions, common around the world? What about women who choose to give birth being abandoned and left impoverished by fathers who think the baby was her choice and not his? There are plenty of things that could be listed here, just as recounting which wars are clearly not justified is an easy exercise.

It just struck me as odd to observe that pacifists who are used to dealing with arguments about extreme cases and therefore using either or both of these two responses about other kinds of violence would then turn around and use the extreme-individual-cases technique on abortion.

Problem 2: Religious Differences

My branch of Quakers, unlike the evangelical branch, tends toward an interfaith understanding. I’ve written on the importance of interfaith understanding for peace. There is “that of God” in everyone, and therefore reaching that of God in each person is helped by being respectful of their religious understanding. Also, we have no creed, because a creed tries to put reality in a box and truth doesn’t fit in a box. There’s always “yes, but . . .” and other nuances plus alternative perspectives.

My branch of Quakers, unlike the evangelical branch, tends toward an interfaith understanding. I’ve written on the importance of interfaith understanding for peace. There is “that of God” in everyone, and therefore reaching that of God in each person is helped by being respectful of their religious understanding. Also, we have no creed, because a creed tries to put reality in a box and truth doesn’t fit in a box. There’s always “yes, but . . .” and other nuances plus alternative perspectives.

So some Friends argue that different religions have different ideas of when life begins. Therefore, they think it follows that we allow those who think it’s later than conception to be able to kill those already conceived. That’s my wording rather than theirs, of course. It gives my first idea of what’s wrong with this approach.

But more to the point, if there’s anything that different religious groups disagree on, it’s the military. A lot of religions favor defensive “just” war, and many favor aggressive “holy” war. Plenty of soldiers actively engaged in war are very religious indeed, and will use religious justification for what they’re doing. Yet pacifists, by definition, take a stand against war. We don’t make arguments about religious pluralism to keep us from doing so.

And when the life of an individual human being begins isn’t a religious question. It’s a scientific one.

Problem 3: Conscience Rights

We normally apply the idea of conscience rights to objection to war. Many Friends may then be sympathetic also with those with conscientious objection to abortion, but I don’t know since I haven’t used that point much.

But there have been those who’ve applied the conscience principle this way: women should have the right to have abortions after consulting their own consciences.

But if a man’s conscience has him picking up a rifle to go to war, I say that there should be no war for him to use his conscience to fight in. And if the war is there all the same, I’ll try to talk him out of participating. I’ve never understood conscience rights to cover actively killing – only refusing to kill. After all, I’m a pacifist.

I also object to leaving a mother dangling as if she’s isolated and on her own. There’s always also a father, there are grandparents, there are employers and social workers and some incredibly callous social policies. People whose consciences allow them to pressure mothers into abortions are people whose consciences need more care.

===========================================

For more of Rachel’s posts on similar topics, see:

The Civil War Conundrum, 150 Years Later

Would Nonviolence Work on the Nazis?

The Darkest Hour: “Glorifying” War?

Extreme cases: Who is to decide that the mother is better off going through labor and watching her baby die? There are individual responses to grief. Maybe you would prefer to hold your baby, but not all would.

Religious differences: Scientifically, the beginning of life is a first-cause issue. The Catholic-dominated court has no business imposing its view on Jews who do not believe life begins at conception.

Conscience rights: You can argue for or against war for any soldier to grapple with. You cannot argue for or against reproduction for any woman with a problem pregnancy to grapple with.

The U.S. government is secular. It needs to operate on the basis of scientific fact. Almost all embryologists agree that the science is clear that life begins at conception. Before science became clear, one could accept that different religious groups have different beliefs on when life begins. But once the science is clear, the government must rely on scientific facts. If your faith believes in human sacrifice, those committing the act are subject to legal penalties for murder. Their religion is not a Get Out of Jail Free card.

Interestingly, neither the Dobbs majority, nor the Dobbs concurrences, nor the lengthy and passionate Dobbs dissent, claims in any way that opposition to abortion comes from religious dogma. Instead, all sides appear to recognize that it comes from a rational understanding of the undisputed facts of human gestation. The issue in dispute is solely whether freedom trumps life or life trumps freedom. So the fist vs. nose analogy is a good one.